There are no photographs of Saadeh’s return to Lebanon by sea in 1930, for he was not yet known except to a few relatives and friends. He came carrying an ambitious project for his country, determined to found a strong national party capable of implementing its program—one that would lead to his nation’s independence, revival, and progress among the nations. Independence, for Saadeh, was not an end in itself, but the necessary passage toward building his nation, which he envisioned on the following foundations:

First, the necessity of establishing a national state after the collapse of the religious empires and the fall of the Ottoman Sultanate, in a world that had adopted the nation-state model, where the people are the ultimate source of authority.

Second, the need to separate religion from the state, for religion is, at its core, a spiritual message aimed at the salvation of the soul. The state, on the other hand, is responsible for administering society’s affairs on scientific foundations. The state, therefore, requires specialists from various fields who can keep pace with global developments, enabling their society to survive, progress, and flourish. Furthermore, the separation of religion and state ensures a just society in which all groups are represented without any feeling of injustice or humiliation. The most essential aspect is the elimination of religious divisions and blind fanaticism. In this regard, Saadeh addressed his followers during the sectarian clashes between al-Najjada party (muslim), and al-Kataeb party (Christian) in 1936, urging them to go to the streets and form a barrier to separate the two sides:

“Turning the homeland into a field where a single people, united in destiny, is split into two armies fighting to achieve one end—the national ruin—is a disgraceful act befitting only barbaric peoples" (Collected Works, vol. 2, pp. 54–55)

Third, the prevention of racial, ethnic, or sectarian discrimination among the elements residing within the homeland, since all are equal in citizenship and before the law.

Fourth, the removal of all barriers that stand in the way of full equality between men and women in national rights and duties.

In this vision, Antun Saadeh drew upon his father, Dr Khalil Saadeh, who had founded a party in Latin America called the National Democratic Party, which espoused the unity of Bilad al-Sham (Geographic Syria) based on a democratic federal system (Al-Rabita, p. 153).

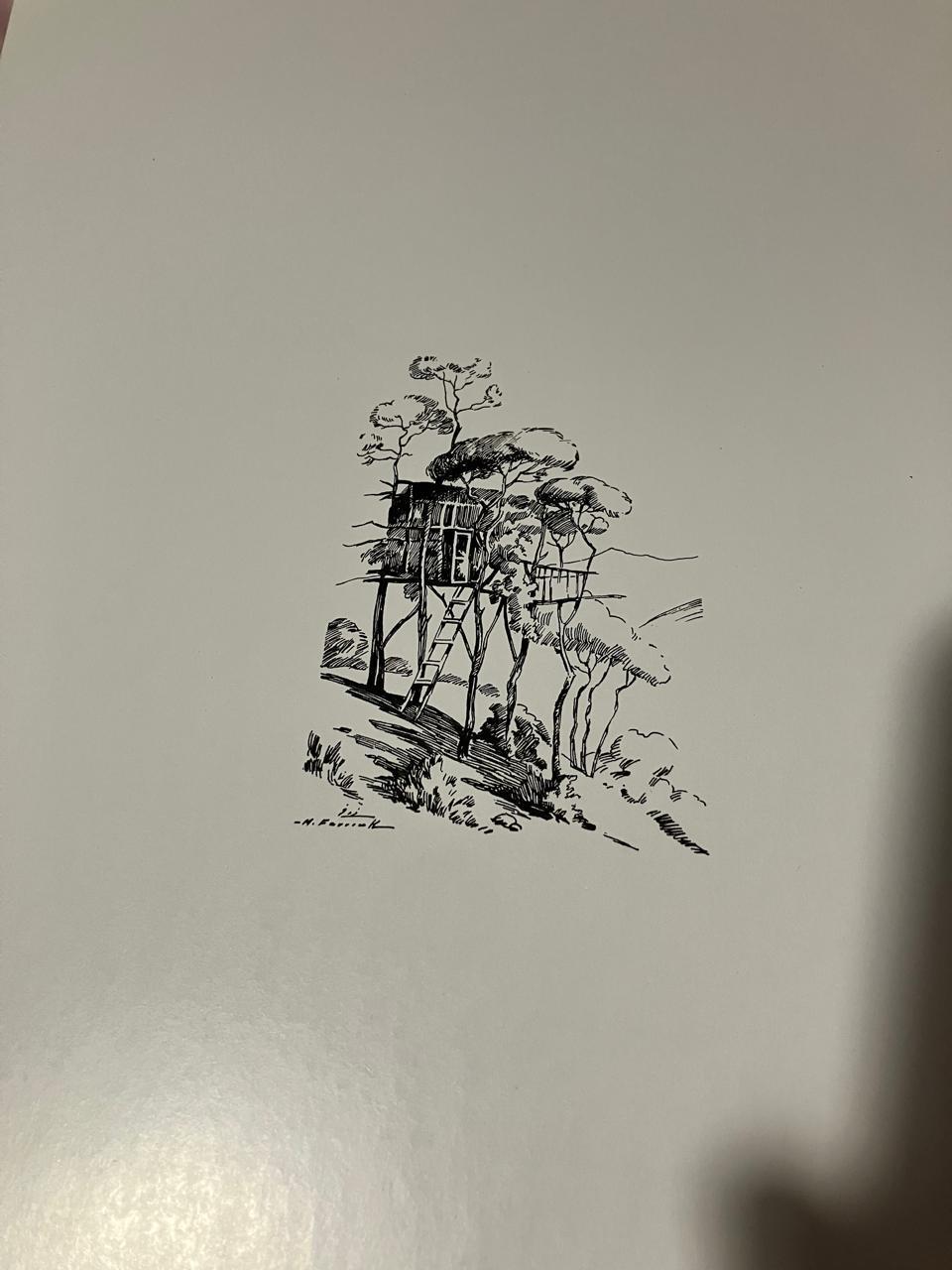

Saadeh returned home with nothing but his dream and his grand national project. He possessed no wealth or position—only his own energy and personal effort. Upon arrival, he went straight to his village, Dhour el-Shoueir, nestled beneath Mount Sannine, and built a small tree house (Arzal), made of pine wood and branches. It consisted of a single bedroom and a spacious balcony that could accommodate relatives and friends.

Saadeh loved nature. He slept peacefully in his treehouse, bathed in the nearby spring, and ate oats with milk brought daily by milk vendors heading to the nearby monastery. There, in that spot overlooking majestic Mount Sannine on one side and the deep blue Mediterranean sea, on the other—with rolling hills and pine and oak forests in between—Saadeh spent some of the happiest days of his life. He read, wrote, and laid the first foundations of the great mission he had set for himself: the establishment of the Syrian Social Nationalist Party.

He later went to Damascus, where he spent a year writing for its newspapers, lecturing in its forums, and engaging in discussions in support of his cause.