This adolescent could not understand why “they” were supposedly better than “us,” or why they appointed themselves as bearers of “civilization,” selling it to those they imagined to be ignorant, backward, barbaric, and savage societies. Born in 1904 as a Syrian — since “Greater Lebanon” did not exist before the French entered and, with British assistance, tore apart Bilad al-Sham — Antun Saadeh grew up questioning that arrogance. Great Britain, whose decline his father, Dr Khalil Saadeh, foresaw, was described by him in 1931 in these words:

“Britain and France will awaken to the dangers surrounding them when another world war breaks out, and that immense war will mark the beginning of the disintegration of the British Empire.” (Al-Rābiṭa Magazine, Issue 222, March 3, 1934).

Saadeh’s childhood embodied the tragedies of all the children of the Fertile Crescent — displacement, hunger, destruction, and the disappearance and scattering of family and friends across the world in search of safety and stability. The Ottoman Empire neither provided prosperity nor progress sufficient to keep its people in their homeland; it monopolized trade routes from the Far East, diverting them through Istanbul to the West, and proved incapable of defending its empire against Western expansionism aimed at seizing raw materials such as oil. Thus, Western domination took hold — preventing the region’s recovery by dividing it, weakening it, subjugating it, and turning its people into slaves on their own land, consuming the products of the West’s vast industrial machine.

At the end of the First World War, Antun Saadeh and his siblings went to stay with their maternal uncles in the United States, awaiting news of their father, who had been forced to leave Egypt after supporting the ʿUrabi Pasha revolution. When Dr Khalil Saadeh finally settled in Brazil, he asked his children to join him there.

Dr Khalil Saadeh had graduated as a surgeon in the last quarter of the nineteenth century from the Syrian Protestant College (now the American University of Beirut), alongside such illustrious contemporaries as Yaʿqub Sarruf, Bishara Zalzal, Shibli Shumayyil, and Jurji Zaydan — names that would later shine across the Arab world in politics, literature, medicine, and journalism.

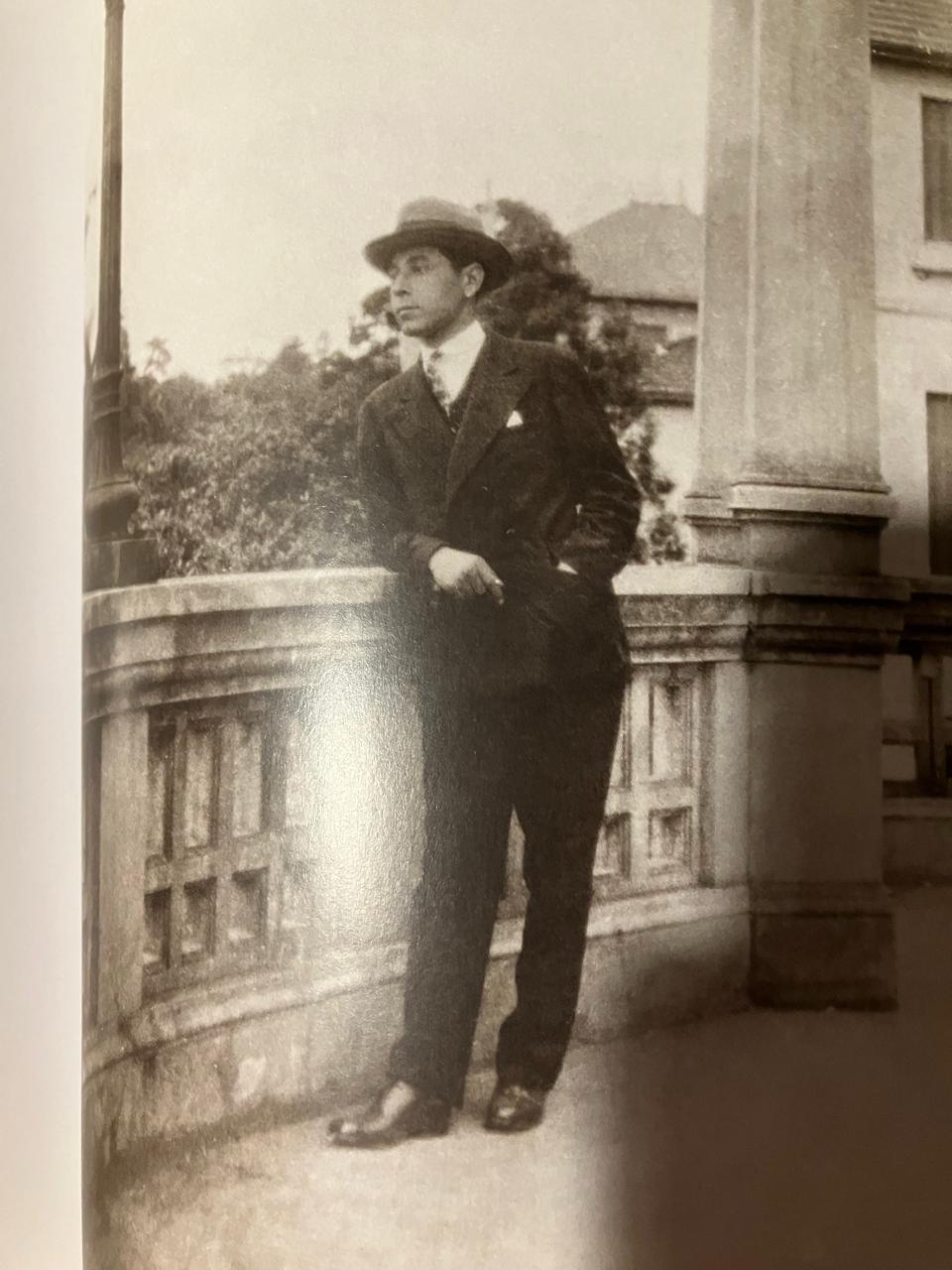

Antun Saadeh could never forget the tragedy of his homeland, nor could he abandon the nation he regarded as his own mother. He refused to adapt to his new environment; as long as his country remained unwell, he too could not be well. He immersed himself in the study of history, sociology, and international politics, devouring everything related to the building of national and social states — theories of governance, systems of society and citizenship, economics, and international relations.

A special bond grew between Antun and his father, who decided to abandon the medical profession altogether and dedicate himself to writing. Together — father and son, working entirely alone without assistance — they founded and published a political newspaper. Antun even learned typesetting, composing his articles directly by arranging the letters in print. Both devoted their lives to enlightening their compatriots and guiding them toward the path of deliverance — the path of building a national state, the only force capable of confronting Western power and arrogance.

Just as the father had renounced a prestigious and comfortable life befitting his medical career — he had, in fact, headed a hospital in Acre before leaving for Egypt — the son likewise abandoned all material ambition. He chose a life of austerity and utter simplicity, never pitying himself for a moment, having made an irrevocable decision:

“I must forget my own bleeding wounds so that I may help to heal the deep wounds of my nation.” (Collected Works, vol. I, p. 43).